Ski patrollers are an odd amalgamation. Part professional skier, laborer, explosives specialist, first responder, coach, sex symbol—they wear many hats. So, it makes perfect sense a few patrollers would add avalanche dog trainer to their requisite skill set. And it’s nothing new. For nearly half a century scores of ski patrols have used dogs as a part of their avalanche rescue plans throughout the mountain ranges of North America. And for good reason. The nose knows.

Let’s lay out some basic groundwork. Dogs are not usually considered part of companion rescue. They are trained to be a vital tool for organized rescue organizations like ski patrols and Search and Rescue teams to locate victims such as buried skiers, snowmobilers, hikers and climbers. Often, they are dispatched to avalanche sites with helicopters as part of larger rescue units.

According to stats compiled by the Phoenix Veterinary Center, a dog’s nose is powerful enough to detect substances at concentrations of one part per trillion—a single drop of liquid in 20 Olympic-size swimming pools. With training, dogs can sniff out drugs, bombs, locate dead bodies, pursue suspects, and detect human diseases like cancer, diabetes, tuberculosis, and even malaria—from smell alone. So, why not use them for locating individuals buried in avalanches?

Over the last decades, we have seen a proliferation of rescue equipment and protocols to better protect skiers and riders who venture into avalanche terrain. We have digital avalanche transceivers with marking functions, collapsible shovels, probes, Recco® reflector chips built into clothing, avalanche airbags, strategic shoveling and probing techniques—all manners of technologies that have origins in the last 40 years.

But this wasn’t always the case. Early avalanche beacons were pretty primitive, used a single antenna, an earpiece, and had a range of about 27 meters. Shovels and probes were large, cumbersome, and were not readily available, and skiers didn’t often tour with them. Now compare that to about a couple hundred thousand years of biological evolution that has taken place within the 3-6 inches of a dog’s olfactory system. There’s no comparison.

You see, dogs have around 300 million olfactory receptors in their noses, which is about 294 million more than we have. Also, the area of a dog’s brain devoted to analyzing those odors is about 40 times bigger than ours. A dog’s nose also functions quite differently than our own. When we inhale, we smell and breathe through the same airways within our nose. When dogs inhale, a fold of tissue just inside their nostril helps to separate these two functions.

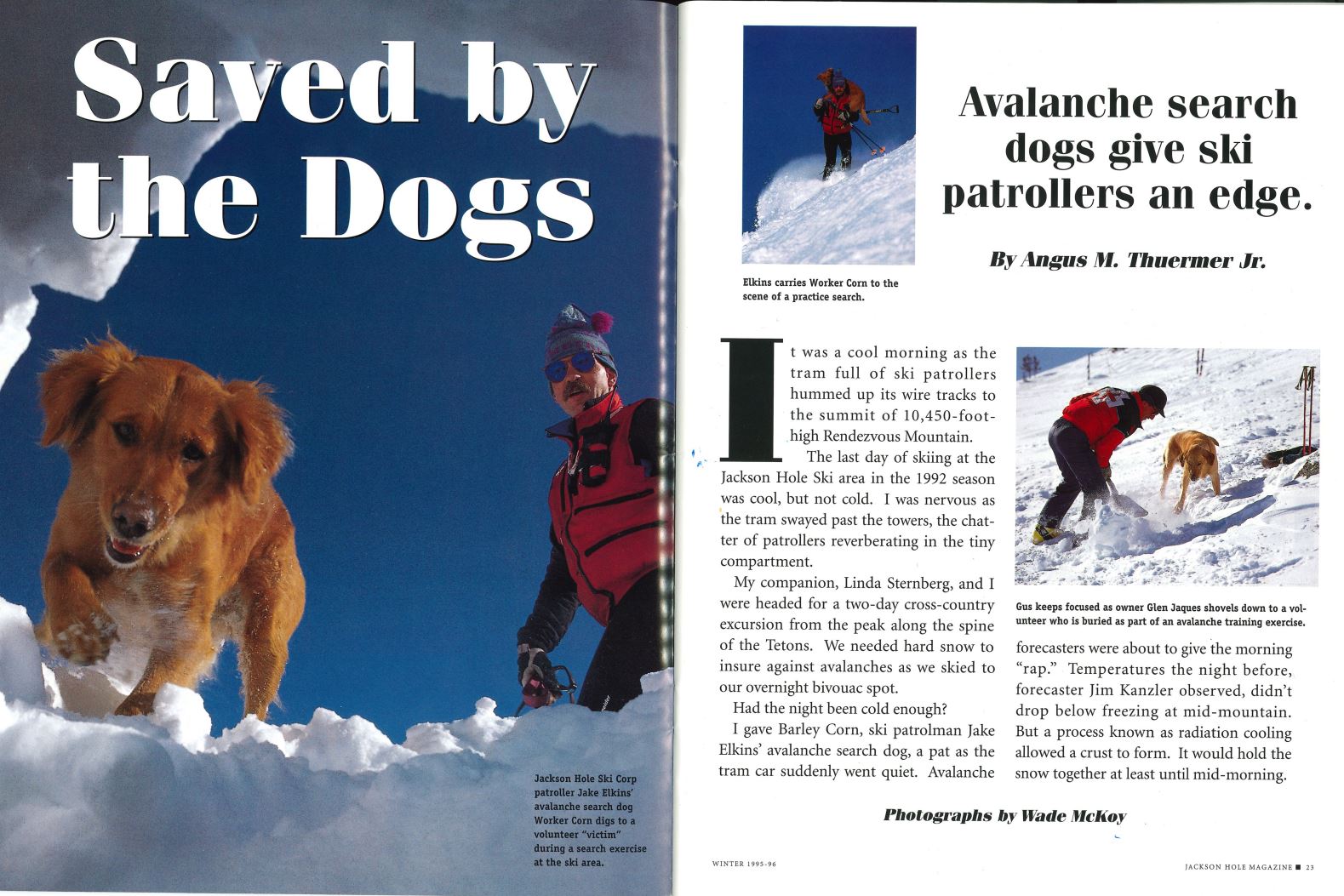

That’s one reason dogs can systematically clear a large swath of avalanche debris far more quickly and thoroughly than a team of a hundred rescuers with avalanche probes. And that value is at the heart of avalanche dog programs. Many slides happen and dogs can validate if someone is in the slide or not. “A lot of peace of mind is what the programs have done for a long time,” says Jake Elkins, former JHSP Director, and veteran dog handler. “Dogs can take a lot of the guesswork out of the equation, which, essentially, is confirmation work… that nobody is in there.”

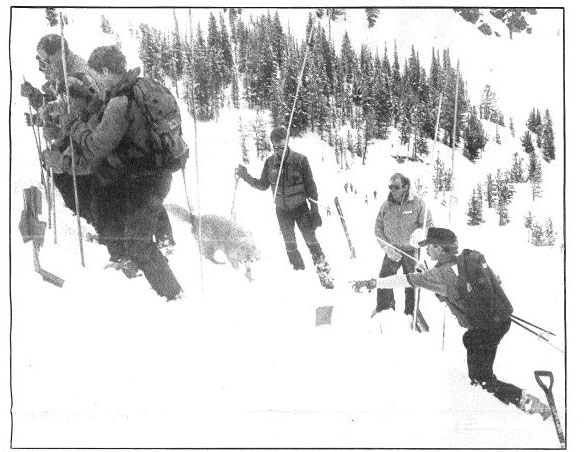

On April 1, 2021, a snowboarder was caught, carried and buried on Taylor Mountain, a popular backcountry skiing destination on Teton Pass, Wyoming. His partner, unable to locate him with an avalanche transceiver (sadly, the victim’s wasn’t turned on), made her way out the Coal Creek parking area, where she then called for professional help. Search and rescue personnel battled adverse and dangerous conditions that afternoon, though dozens of volunteers arrived and began probe lines and searched for clues. At nightfall, efforts ceased until morning, where a Heli-bombing mission (to protect the rescuers from lingering avalanche hang fire) was a part of the continued rescue force, after which, probe lines of rescuers and drones resumed combing the debris.

Jackson Hole Ski Patrol was able to get a dog team on scene around 11:30 am that next morning. Patrolman Peter Linn arrived with his dog Goose, a border collie. Searching a probable location to where the boarder’s body might be found. Linn, alongside many other rescuers, was well aware there was still weather and avalanche danger to the rescue efforts despite the Heli mission. Many, including the Teton County Sheriff, were concerned rescuers would be exposed to that hazard for at least the rest of the day and possibly into the next morning, given the circumstances.

However, Linn set Goose to task, and she took all of about three minutes to pick up the scent and find the body. It’s a traumatic day no matter how you see it, but the ability of Linn’s trained dog to zero in on a location in mere minutes is what brings true value and credibility to professional search dog programs. “We were at the toe of the slide,” says Linn. “A lot of people thought he was going to be higher in the slide, but luckily he wasn’t.” Not only did Goose do her job, she prevented scores of rescuers of having to remain in hazardous terrain for potentially hours if not days. What a dog can do in saving time and exposure in those situations is invaluable to the safety and well-being of SAR members.

Jackson Hole’s Avalanche Dog Program dates back to 1979 and a patroller named Peter Mackay. “There was this one lady who was doing [avie dog stuff] in Washington,” remembers Mackay. “And she had this German Shepherd she was training. She got a hold of us, and asked Dean Moore (then Jackson Hole Ski Patrol Director) if she could come and see us. We didn’t know why at the time.” In fact, when she did arrive for the demonstration, Mackay wasn’t that impressed. “I didn’t think the dog was that well trained,” he admits. Nevertheless, her name was Sandy Bryson, and her seminal book Search Dog Training was published in 1984 and long-considered the go-to for aspiring search dog handlers.

“I grew up with field trials dogs,” says Mackay, who spent his adolescence in Jackson. “My dad was one of the top field trials guys in the country.” So, regardless of any criticism, Mackay knew Bryson was definitely on to something. “I got a hair going right then and there,” he says. “I can do this. And that summer I picked up a lab puppy.

Jackson’s dog program, like so much else, started with a few seeds like Mackay, some luck, tenacity and drive. “My most satisfying moment with dogs was the first day we took out Seal (his first black lab). It was Laramie Bowl, and it was my challenge to show the guys. I told Dean I was ready to take her out and show them what she could do.”

It was during mountain setup. The Laramie Cliffs had produced a large slide down the bowl, a perfect venue for Mackay and Seal. Mackay buried a co-worker far down the slope in a dog hole and no other clues. If that wasn’t enough, the Teton County Sheriff’s Dept. was also on hand to see if Mackay’s dog had the chops.

“There was a crowd,” remembers Mackay. “And nobody could believe this dog could do it, especially a one-year-old lab.” Yet, within minutes, Seal zigzagged down the slope, picked up the scent and began digging out the buried troller. “And, son-of-a-bitch, she did it,” he laughs. “She pulled it off.”

How she pulled it off can be further explained by science. Dogs can wiggle their nostrils independently. You and I cannot. Along with the fact that the proverbial aerodynamic reach of each of their nostrils is smaller than the distance between the nostrils, this helps them to distinguish which nostril an odor arrived in. This is a serious advantage to helping them locate the source of smells—like people buried in the snow.

Scent on the ground travels a meter for about five minutes, according to Mackay. “Wet snow is a lot slower,” he says. “Cold snow is dry; it’s a lot quicker. So, you’ve got those principles to work with. Once the scent is up, even though no one’s disturbed it, the dog knows so. And that’s what Seal was about. She could find the scent in the air, and work the ground.”

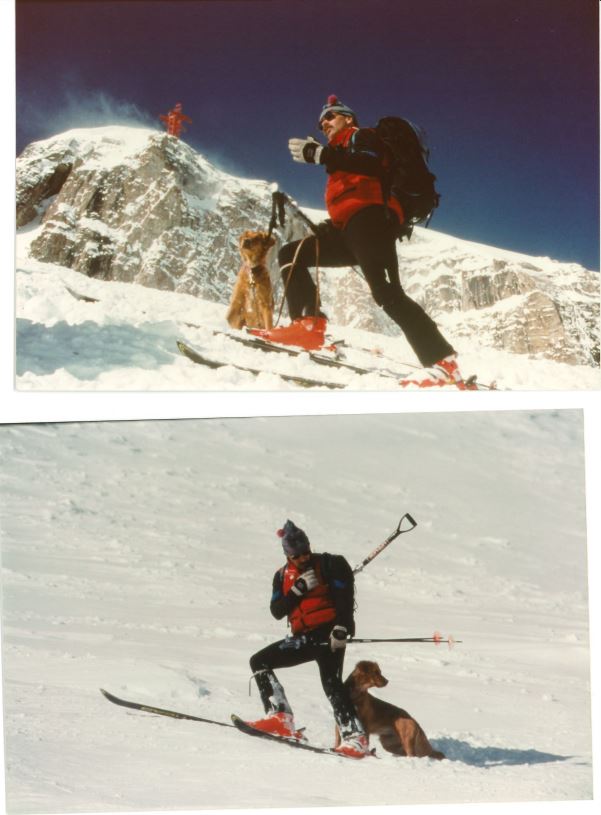

So, how do you pick a puppy to become an avalanche dog? “We broke from the norm in Canada and France,” says Elkins, where the German Shepherd and Belgian Malinois were the dominant search breeds. “We went with the retriever breeds for ease of training; they will respond to multiple handlers, have an excellent sense of smell and their qualities as hunting dogs.” For his part, Elkins was the second patroller to join the program, soon followed by Jerry Balint, himself a veteran of field trails labs.

“We mostly preferred females for their smaller stature, speed and agility,” says Elkins. “Our program is set up so the handlers own their dog. They get a paycheck, insurance, and they go home with the handler. If an owner gets sick or injured, being trained in the ‘multi-handler’ setting allows the dog to still come to work.”

For instance, Elkins’ wife, Carrie, also a handler, ended up injured one season, while her dog Douce still went to work each day, training with the other handlers. She was also the only ski patroller to take her dog, Rosie, on the annual French patrol exchange. “That was super eye-opening,” she says. “They all had these big, macho German Shepherds—all male—and didn’t care if they bit people. And I showed up with this little black lab. But by the time I left, a bunch of people said I had the best avalanche dog in Tignes.”

“Jackson Hole is somewhat known for the little black lab,” says Scott Stolte, Asst. Patrol Director, and lab enthusiast. “If you go to other patrols, a lot of other dog programs out there, when they think of Jackson Hole, they think of little black labs. They’re a great tool. Obviously, it comes down to personal preference or different flavor, and whatever your flavor is, they’ll do a great job. I just like labs: they’re happy, friendly, they love it, love the job, and they do it very well.”

Long-time patroller and handler Rick Frost has had four labs himself, but like Stolte, is more interested in simply appropriate breeds and appropriate drive. “We put a lot into our breed and puppy selection,” he says. “I’ve always thought that was really important. If you start with the best product, the best clay, you can come out with the best sculpture in the end. And, we’ve seen of lot of breeds that are just awesome. Border Collies are phenomenal, the smartest breed on the planet, hands down; easy to train, great drive, super smart. Those dogs can learn to do anything. And Chris’s [Brindisi, former Director of the JH Dog Program] new Shepherd, his dog now, wow, she’s a monster, really good.”

In 40 years, the program has had 18 Labrador Retrievers, five Golden Retrievers, one Flat-Coated Retriever (think: black Golden Retriever), two German Shepherds, one Dutch Shepherd, one Boykin Spaniel, one Border Collie and one Airedale.

In addition to basic obedience training—sit, stay, down, come, heel—specific training for avalanche rescue dogs begins as simple games of Hide and Seek in the home whereby the puppy is taught to go find their favorite toys and progress to find people inside the home. As they gain confidence, the game goes outside, using people as the quarry, hiding out-of-sight behind trees, bushes and in ditches.

Once there is ample snow to hide a person, the real fun begins, according to Elkins. “We start with the handler running away from the dog and going in a snow cave (quince) with the entry left open. This is followed by a succession of drills where the handler takes control of their dog and another person becomes the quarry. This continues up to a point where the entire entrance is fully packed with snow and the dog has to dig through entry to get contact with quarry. The reward is tug of war with a burley rag and great enthusiasm on all parts (dog, quarry and handler). Generally speaking, with all training the reward is lots of praise, lots of treats, lots of love.”

It all sounds great, but there are challenges. Chris Brindisi knows that training a search dog is a serious investment, and things don’t always work out. “There are nuances to the job and dog handling,” he says. “You have to treat your dog like they’re your best friend, and also treat them as a tool. And, you might have to put your best friend in harm’s way. Or, if your best friend can’t do the job, you have to remove the tool from the program if they’re not performing at the requisite level.”

It’s not an easy thing to do, reminds Brindisi. “But that’s the job,” he says. “And I feel fortunate to be able to involve my dog with work, and contribute to the team and overall effort of our job.”

Logistics are yet another factor, according to Bill Vore, Jackson’s new dog program coordinator, “You have to find time to work with the dogs but also try to feel like you’re a part of the daily operations of the ski patrol,” he says. “From my eyes, I’m trying to balance the two: trying to get as much dog work, but be involved with other aspects of the ski patrol world I fell in love with a long time ago.”

And with that are the associated rewards and positive feedback. “The possibility that you could help bring closure to a really crappy situation,” he says, “or maybe get lucky as hell and find somebody alive.”

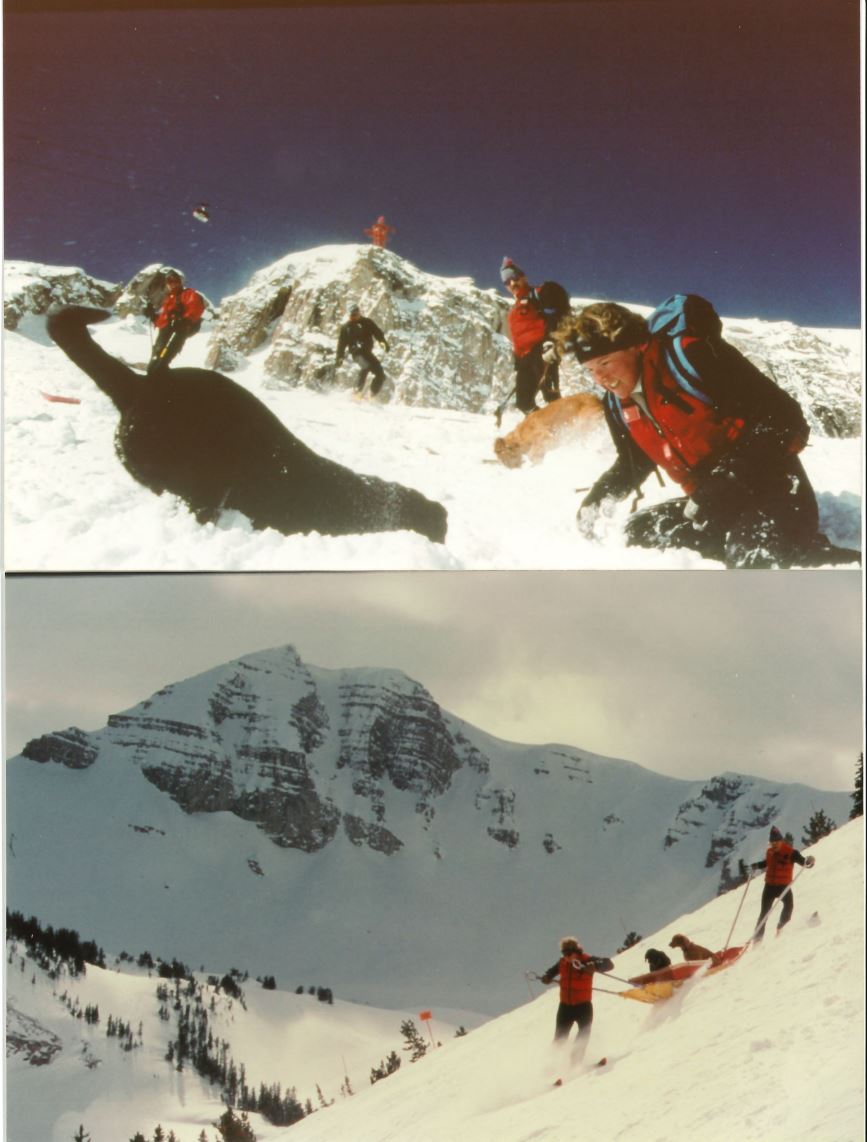

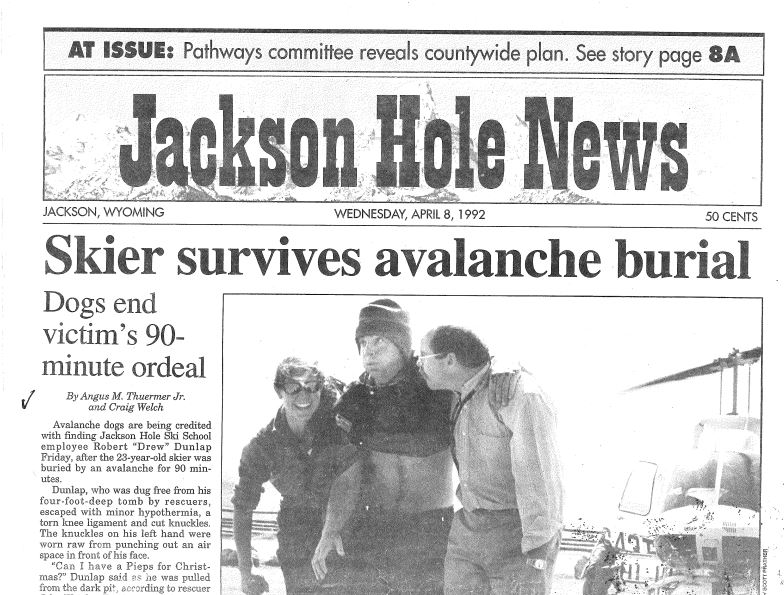

Which has happened. At 10:03, April 3, 1992, an off-duty Jackson Hole Ski Instructor and a companion were caught in a backcountry avalanche initiated from above by a third member of their party. The slide carried Drew Dunlap 900 vertical feet and buried him four feet deep near the toe of the path.

At that time, patroller Suzanne Hagerman was riding Sublette Chair lift, witnessed the avalanche in the Rock Springs drainage just outside the resort, and promptly radioed to Mountain Station.

“He went over two cliff bands,” says Rick Frost. “Both of them about 50 feet high. Since he was in the middle of the slope, the slide more or less moved like a flying carpet, and simply carried him over each one.”

“We immediately called Pilot Ken Johnson,” says Elkins. “Fortunately, he was at the airport. However, he was doing maintenance and the dashboard was completely out of the ship, so we had a 45-minute delay. He picked us up at Mountain Station, we let Frosty and [his dog] Rage out at the top of the slide, and Balint/Coup and myself/Barley dropped off at the toe.”

The wet slide had run full track and it was very warm, approaching 60 degrees. “Jerry and I stripped down to our T-shirts,” says Elkins. “We no sooner got on the bed surface, and within seconds both dogs had strong indications. There was a group of people probing around some trees above us that we called out to help.”

Elkins locked eyes with another rescuer as they heard a muffled call for help. “Did you hear that?!” he remembers saying. “Then we heard Drew again under the snow.” Elkins kept the rest of the group back while Jerry reset Coup. She split the difference between the dogs’ first two indications, pinpointing what turned right to Drew’s face in a small air pocket with a crack in the debris that lead to the surface.

“Coup made about three coyote bounds and landed right on the head,” says Frost. “And that was it.”

From Hagerman’s initial call, to the moment he again saw the light of day, Drew Dunlop was buried 1 hour 33 minutes. In addition to the search, a spring snowpack with fissures and cracks had helped in giving him enough passive air that his rescue was even possible in the first place. Luck gave a helping hand that day as well.

That particular slide path is now commonly referred to as Drew’s Slide. What’s more, is that Jerry Balint and Coup are credited with the first successful live find in the field by an avalanche dog in North America. That said, it should be noted that US Forest Service employee Roberta Huber’s dog Bridget, a German Shepherd, found Anna Conrad and saved her life April 5th, 1982, in a building hit by an avalanche at Alpine Meadows Ski Area.

As Jackson’s dog program continues to progress, they have aligned themselves with the Colorado Rapid Avalanche Deployment, or C-RAD, a formal, educational and validation resource for professional dog handlers. “The idea came up, ‘would Jackson be interested in joining with them and being an affiliate member with C-RAD,’” explains Scott Stolte. “Even though we’re not in Colorado, I think they liked the fact that we weren’t because it gave their program more depth and broadened it. And it’s great for us to piggyback off them when it comes to validating dogs and having an outside entity that’s a known, trusted industry member to validate with—that further legitimizes our program. It’s beneficial for both parties.”

John Reller, one of the main energy centers behind C-RAD, and the current training coordinator echoes Stolte’s sentiments. “The more that we can work with others outside our area, the better,” he says. “And, it’s not just ski patrols, but lots of agencies that bring together their collective talents so that the standard is always getting higher, always improving.”

Do dog handlers have a common denominator? Maybe. “It’s important to just be a natural dog person,” says Rick Frost. “Some people can just communicate and understand and relate to dogs better than other people. Some people have an affinity for dogs, just have a better feel and can read the dog. A lot of it is just being born out of the love for your dog, and you just build this bond with them and when you start working, give them a job, and they learn to trust you, move in new situations; it just builds this great bond and that’s what starts to drive you as a handler. You start to see success, and you’re hooked.”

Photo Credit: Amy Jimmerson, Stephen Shelesky, Jake Elkins.

The Patrol Dogs are supported by Mammut, Yeti and Nulo Pet Food.