How long does forever last? For Peggy Hays, a visiting skier to Jackson Hole Mountain Resort, forever lasted about 15 minutes on March 1st, 2020—the moment her husband dropped on the slope to the second in which he left the scene in a rescue sled with scarcely a pulse.

The call came into Ski Patrol Dispatch at 12:49 pm that CPR was in progress somewhere on South Pass Traverse. Now this should come as no surprise to anyone that a heart attack halfway up a mountain is less than ideal, not that anyone has ever made the case for a convenient heart attack—the gravity of the situation is quite obvious. Nevertheless, there is a plan, and ‘CPR in progress’ over the airwaves puts that plan into motion.

Jim and Peggy Hays graciously gave us permission to relive their story, not only as a teaching tool for all of us in the outdoor medical field, but because it’s a relevant anecdote of luck favoring the prepared when it matters most, and an individual who beat unrelenting setbacks after undergoing such an affair. I was able to interview several key players who were a part of this event to put together a timeline and story of how Jim Hays transcended a life-altering experience.

Jim and Peggy live outside Sacramento, CA, where he owns a global consulting firm that advises the High-Tech industry on how to sell more effectively. As a younger man, he flew in the Air Force as a navigator and achieved the rank of Captain. While serving, he earned his private pilot’s license, and since then has acquired an instrument rating and is qualified to fly seaplanes. Until recently, he flew often. He has been a PADI-certified SCUBA instructor since his early 20s, freediving over 200 feet below surface on multiple occasions, and doing things like night dives with manta rays. (Or, as l like to say: nope.) He’s also logged 400-plus freefall jumps as a sky diver. He’s active, traveling across the globe with Peggy, and really not what you’d consider a likely candidate for an on-mountain heart attack. Yet, there he was.

“It was the second time we’d been to Jackson Hole,” he says, “riding behind the draft horses, feeding the elk, doing all these iconic things; the scenery, being on top of the mountain. What we jokingly tell everyone is we had an absolutely awesome time… Right up until the point where we didn’t.”

“We hit the lift and he wasn’t feeling that great,” says Peggy. “So, I told him that I bet you’re probably hungry, so let’s go down for lunch. Then we took that cat track, and that’s where I waited for him. He stopped about six feet from me and said, ‘Babe, I don’t feel so good.’ And then he just fell like a tin soldier. The whole time I’m thinking, ‘is this low blood sugar? If it’s a heart attack, you’re not supposed to be seizing, and he was seizing, foaming at the mouth.’” She began yelling for someone to call 911.

Peggy herself is a certified anesthetist by trade, who manages airways for a living, and has participated in countless codes on the operating table. “He was still moaning, was still moving air,” she says, “so I just got his tongue, opened the airway, and just used my thumbs to jaw thrust. He was still breathing at that point. I checked his carotid artery and he still had a pulse. In these split seconds, I’m thinking ‘What the Hell is this!?’”

Sheer randomness plays a large role in all of our lives. Dr. Jacob Chapman, an emergency room physician on vacation from Massachusetts, can relate. His group was on South Pass Traverse exactly when Peggy witnessed Jim crumble. They skied upon her struggling with him less than a minute after he went down.

“I moved through the crowd,” says Chapman, “and Peggy was at Jim’s head, and she was keeping his airway open, and he was just rolling around on the ground moaning, and not able to talk. With one ear I was kind of listening to what she was saying. Someone else said he had a seizure. Peggy said he stopped on his own, then just collapsed. It was amazing to see how well she was keeping it together.”

Chapman knew it was a heart attack. He reached down to feel a pulse, and heard someone say ski patrol had been called. “Good,” he thought, “that box has been checked.” They kept a close eye on him, but then he stopped moving as much and they lost his pulse. “And we started doing chest compressions,” he says. To be clear, a typical heart attack usually occurs when a blood clot blocks blood flow to the heart. Without blood, tissue loses oxygen and dies.

Jackson Hole Ski Patrol is lucky to have the medical direction of the St. John’s Emergency Medical Physicians Group, a cadre of ER docs, physician assistant, and St. John’s nurses who rotate through the Teton Village Clinic each winter. Dr. Jeff Greenbaum is the main energy center behind our empowered protocols and, along with his colleagues, tailor our ongoing training to better suit the potential needs of guests in distress. “What we’re trying to do,” says Greenbaum, “and what I’m specifically trying to do, is make a judgment of what I think would actually help an individual on the mountain versus an individual who’d be better being brought off the mountain. And once we’d identified those things that we can do really well on the mountain to benefit people, I then concentrated on drilling it into you guys (patrol) so that when it happens, and people respond, their reaction is, ‘Hey, I know what I’m doing’.”

It makes for an enviable continuity of care that’s shared from first responder to physician. “When you talk about the seamlessness of the integration with the Clinic and us, EMS, and St. John’s Hospital,” says Ian Barwell, an ER nurse and patroller on scene with Jim’s event, “we have medical direction coming from exactly the people (DR. Greenbaum and Co.) we are bringing patients to.”

Let me give you a rough sketch. Outdoor Emergency Care, the medical training required for ski patrolling in the US, is essentially an EMT Basic certification with an outdoor emergency focus, minus the ambulance experience. The St. John’s ER group has taken the time to augment that training by providing JHSP simple ancillary protocols that allow for slightly modified levels of care on the hill in those initial critical moments of medical emergencies. And it’s that kind of forethought that gives people like Jim Hays the edge when misadventure comes crashing.

“So,” continues Barwell, “the Clinic knows exactly what’s going on with our protocol because they teach us that protocol. When they hear ‘CPR in progress’ they know to get the show ready.”

The reality of heart attacks in the field isn’t uplifting. The American Heart Association says the incidence of EMS-assessed, non-traumatic, out-of-hospital cardiac arrests (OHCA) of people of any age is estimated to be 356,461 annually, or nearly 1000 per day nationwide. Survival is about 10%. Like many ski resorts, Jackson Hole does have procedures and tools with which to address medical emergencies but the facts don’t bare out favorable results no matter where that emergency takes place. Still, early execution of skills and tools can make a difference. “Early activation of EMS (emergency medical services) starts that chain of survival,” says Rachel Kunkle, a patroller present on Jim’s medical arrest.

The other consideration is simply luck of the draw when it comes to heart attacks. “What one hopes for when someone loses their pulse,” says Dr. Chapman, “is that they have a shockable rhythm, like Ventricular Fibrillation (VFib) or Ventricular Tachycardia (VTac) because their rates of survival are significantly higher than non-shockable rhythms like asystole (flatlines, meaning no cardiac activity) or PEA (Pulseless Electrical Activity).”

Ventricular fibrillation is a heart rhythm problem that occurs when the heart beats with rapid, erratic electrical impulses. This causes pumping chambers in your heart (the ventricles) to quiver uselessly, instead of pumping blood. VFib causes blood pressure to plummet, cutting off blood supply to the vital organs. It is the most common cause of sudden cardiac death. And the emergency treatment includes quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and shocks with an AED. The difference with ventricular tachycardia is that the heart continues to beat regularly, but it goes so fast that it never gets a chance to fill with blood. CPR helps maintain perfusion to continue oxygenating vital organs when the heart isn’t working, and the AED looks for a shockable rhythm to restart the heart.

ER Docs perform CPR in hospitals all the time, but on a ski run? Not so much. “In my mind,” remembers Dr. Chapman, “I guess we’re doing this ACLS (Advanced Cardiac Life Support) stuff, but how is this guy going to survive? I was looking around. Where’s the helicopter going to land? Part of my brain was telling me that’s not your part of the problem to solve. That’s ski patrol. They have plans for this.”

According to the dispatch log, at 12:50 pm, Bill Fogarty was the first patroller to arrive on scene, approximately a minute after the initial radio call. Chapman and a friend were performing CPR while Peggy monitored the airway. “Do you have oxygen?!” she asked. “It’s coming,” he said. Soon, a second patroller, Nate Fuller, arrived with an oral pharyngeal airway, and it gets placed in Jim’s mouth.

Chapman was still edgy that the window for this man’s survival was closing fast, but when patrollers started appearing with supplementary oxygen, advanced airway management devices, and an AED, his tune changed.

“And then a sled shows up with a LUCAS®,” he says, “and I’m like, ‘Oh, my God, this guy might actually survive.’” The LUCAS® device is a mechanical chest compression device that helps deliver high-quality chest compressions to sudden cardiac arrest patients in the field, during transport, and in the hospital.

Just like training, patrollers with their specific tools assumed pit-crew positions taught by the ER docs and nurses. “There were many nice ski patrollers who pulled me away from the scene,” admits Peggy, “They were cutting away his clothes, and getting the AED on, and then the LUCAS®. I think they shocked him three times. I don’t remember people talking that much as they were so much in sync with each other, and they just knew what to do. And that’s what it feels like when I’m in the operating room with other anesthetists who I’ve worked with a lot. We don’t even talk. You just know what needs to be done, and it’s done.”

At 12:57 pm, Patroller Rachel Kunkle relays to Mountain Station, “One shock delivered, still working him.”

At 12:58 pm, Kunkle offers a follow up. “Second shock delivered, spontaneous breathing.”

At 13:01 pm, Patroller Megan Raczak radios Mountain Station a third time, “Administered three shocks, three shockable rhythms, and advanced airway in place. About to begin transport.”

“It was impressive how fast the three cycles went,” remembers patrolman Steve Wurm, who was in charge of airway management. “Everything was so sequential. You were never waiting for anything.”

During their interview, Peggy kept reiterating that in spite of the heart attack, how everything else went right that day. “We were on a cat track,” she says, “not a steep slope. We knew that someone could call 911. An ER physician skied up, and then ski patrol arrived with their AED, a LUCAS and King Tube. It was just amazing.”

“We don’t feel like those things happen on accident,” says Dr. AJ Wheeler, the attending ER physician working in the clinic that day. “That’s why we bring King Tubes into the protocol. And why we advocated to have things like the LUCAS® device. We understand why it’s really beneficial, and why we’ve advocated to have these tools available [to ski patrol] for those instances.”

A King Tube a latex-free, single lumen tube with a distal and proximal balloon that occludes the esophagus and oropharynx, creating a direct route for ventilations through the larynx and trachea. “Kings provide better oxygenation and ventilation to the lungs than a simple oral pharyngeal airway,” says Barwell, “There are also better downstream effects, so it’s not just saving his life right now, but also toward survivability and brain function.”

After three cycles of the AED, Jim was taken by toboggan on high-flow supplemental oxygen as the LUCAS Device continued chest compression for the entirety of his transport. He arrived at the base where the hand-off to clinic staff took place. He was immediately put on a monitor where they detected a pulse and organized rhythm. Nurses got IV’s going, pushed fluids, and Dr. Wheeler pulled the King Tube and intubated Jim, which is an even higher level of airway.

Trailing a couple minutes behind, Peggy was escorted to the clinic by patrol where she watched the next chapter of her husband’s recovery unfold. “Watching that code go down,” she says, “And I say this to all the people in our anesthesia department. It was one of the best codes I’ve ever seen. It’s exactly what ACLS should be: nobody yelling, nobody shouting; they we’re just talking in that [calm] tone—a whole team who absolutely knew what they were doing. If there wasn’t excellent work right there at the beginning, he never would’ve made it to Idaho Falls.”

“The real life-saving happened on the hill,” says Wheeler. “To have that equipment show up. And the AED is really what saved his life. That’s what got him going again. And the LUCAS® kept him perfusing in route to the clinic. Once he was in the clinic, he had a pulse. We helped stabilize, for sure, but had he not had those things in the field it wouldn’t have mattered what happened in the clinic.

Once fully stabilized, Jim and Peggy left the clinic by ambulance to St. John’s Hospital. This would mark the beginning of a 33-day odyssey spanning three hospitals and three states. After leaving Jackson, and spending six days in the ICU in Idaho Falls, Jim was then life-flighted to Salt Lake City where he and Peggy began a nearly month-long stay at the University of Utah Medical Center. Jim’s body would endure a heart pump for 11 days, higher than average intubation, an upper and lower GI bleed with an endoscopic clipping, a couple scares of a stroke, and a smattering of CT scans. Plus, his sodium levels remained high and he was retaining 40-50 pounds of water. “And, just to add salt to our wounds,” says Peggy, “he got sepsis from cholecystitis and pancreatitis, adding a midnight trip to interventional radiology for a much-needed biliary drainage tube.”

Get all that? Suffice it to say he passed the event horizon on his way to recovery, just in time for Covid, an earthquake, and while we’re at it, a follow-up heart attack on June 1st, where he once again tested the constitution of his lovely wife.

It builds character. And despite two medical arrests, and an exhaustive month of hospitalization, Jim rode out this whole episode with no anoxic brain damage. “The thing that amazes me the most,” he says, “is that I came out with no mental impairment.” That said, life has changed a bit. He isn’t allowed to pilot planes anymore as a result of his new AICD (automated internal cardiac defibrillator) living in his chest. “I won’t be able to get medical clearance anymore. That’s a no-no for the FAA,” he says. “It’s okay if you die, but they don’t want you to go unconscious because that thing has zapped you.” It’s a fair tradeoff.

“After the fact,” says Dr. Chapman, “I kept thinking about how many needles that guy needed to thread in order to survive that incident… it’s astounding.”

Thankfully, an event like Jim’s is rare, but it is not singular. Jackson Hole has had two other medical arrests on the mountain in the last five years, and we’re proud to say that early activation of EMS on the hill, and intervention by patrol helped to save another individual because of ongoing training and tools like AEDs, King Tubes and LUCAS® devices. After a punishing 2020, I’m happy to be reminded that luck, training and tenacity can still do a little good in the world.

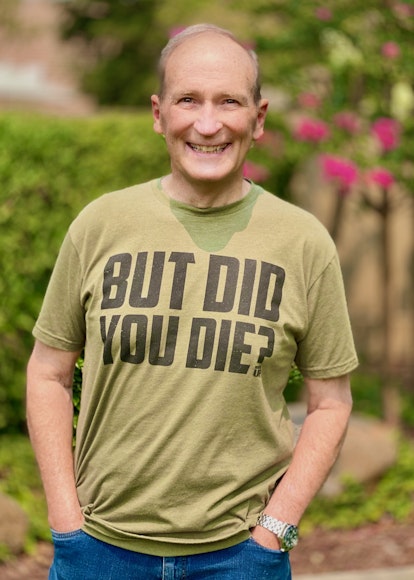

One thing that hasn’t changed much is Jim’s wry humor. In addition to having a wife who now specializes in resurrection, he can often be seen sporting a new T-shirt that says “But Did You Die?” A couple times, perhaps, but who’s counting?

Learn more about the Jackson Hole Ski Patrol here: https://www.jacksonhole.com/ski-patrol.html